I wished I’d known on Mother’s Day a decade ago that I had mere years before Alzheimer’s disease changed my relationship with my mom forever.

“That’s too much money. Let me pay,” my mom said, adjusting her glasses on the bridge of her nose to glance at the bill that the server had just set at our table for two.

“No Mom, this is my treat. I want to pay for this. Please let me,” I replied, and I meant it. She glanced up from the bill to me and smiled, handing it across the table without another word.

“Happy Mother’s Day,” I said.

It was 2010 and we were sitting in one of the fanciest seafood and mimosa brunch locations in Chicago, enjoying a day that we were celebrating together as mothers for just the third time.

I had a job working downtown and lived in Chicago’s Loop area with my daughter, who was two at the time. To spend time with her granddaughter and to help me relieve the cost of big-city daycare, my mom had been taking a 90-minute train from her quiet town in Indiana on Friday mornings to spend the day with my daughter while I was at work. That single day of no daycare saved me hundreds each month — plus it was a good excuse for the two of them to hang out. My mom would stay until I got off work and then spend the night at my apartment.

Our three-generation girl gang would hang out on Saturdays – bundling up for the Windy City elements in the winter months to walk to a nearby museum or library. In the summer, we would stroll down Printer’s Row, arms bare, to find a good place for lunch. After spending several years as a young woman living in Florida, being back so close to home was something I was enjoying thoroughly, especially since it meant my daughter could see her grandparents so often.

This particular Sunday of Mother’s Day I had asked my mom to stay all weekend. I was trying to get ahead on a work project so I put in some extra time on Saturday. Plus the idea of having my mom all to myself on a Mother’s Day morning was too fantastic to pass up.

I reached out to a babysitter I used occasionally who was happy to come spend the morning with my little one so the moms could have the one-on-one brunch time. I had budgeted enough for that babysitter and to take my mom to one of our favorite Chicago spots: Shaw’s Crab House. Of course there were plenty of Mother’s Day brunches to vie for my dollars but I’d been wanting to try Shaw’s famous Sunday morning brunch for months. This seemed like the right time and with the perfect person.

As hard as I tried to act like a normal Chicagoan most of the time that I lived there — silently admiring the Chicago River from the Michigan Avenue bridge and squealing to myself in the lobby of Tribune Tower each day when I arrived at work — on this day, my full-blown tourist zeal was out on display. We oooohed and aaaahed over the spread of lox, crab legs, omelette station fixins and fruit upon fruit. We took a few trips back for more. We refilled our coffee several times.

A few times I looked across the table at my mom, delighted to be drinking coffee with her daughter at such a fancy place, and it felt really satisfying. After 20+ years of her serving as a parent to me — grounding me countless times for the clothing I refused to pick up from the floor, crying when she found birth control pills in my coat pocket when I was 16, waking me Sundays early to go to church and fulfilling her motherly obligation to be at every play, recital, award ceremony and more — at that brunch, we were peers. Two grown women, mothers, acting fancy and enjoying coffee together as they talked about life. It felt really good.

Upon paying that brunch bill, I felt that a shift in our relationship was cemented. Neither needed the other to flourish or thrive but we liked spending time together and we loved our new shared experiences. We were colleagues in life, with the same goals for our families.

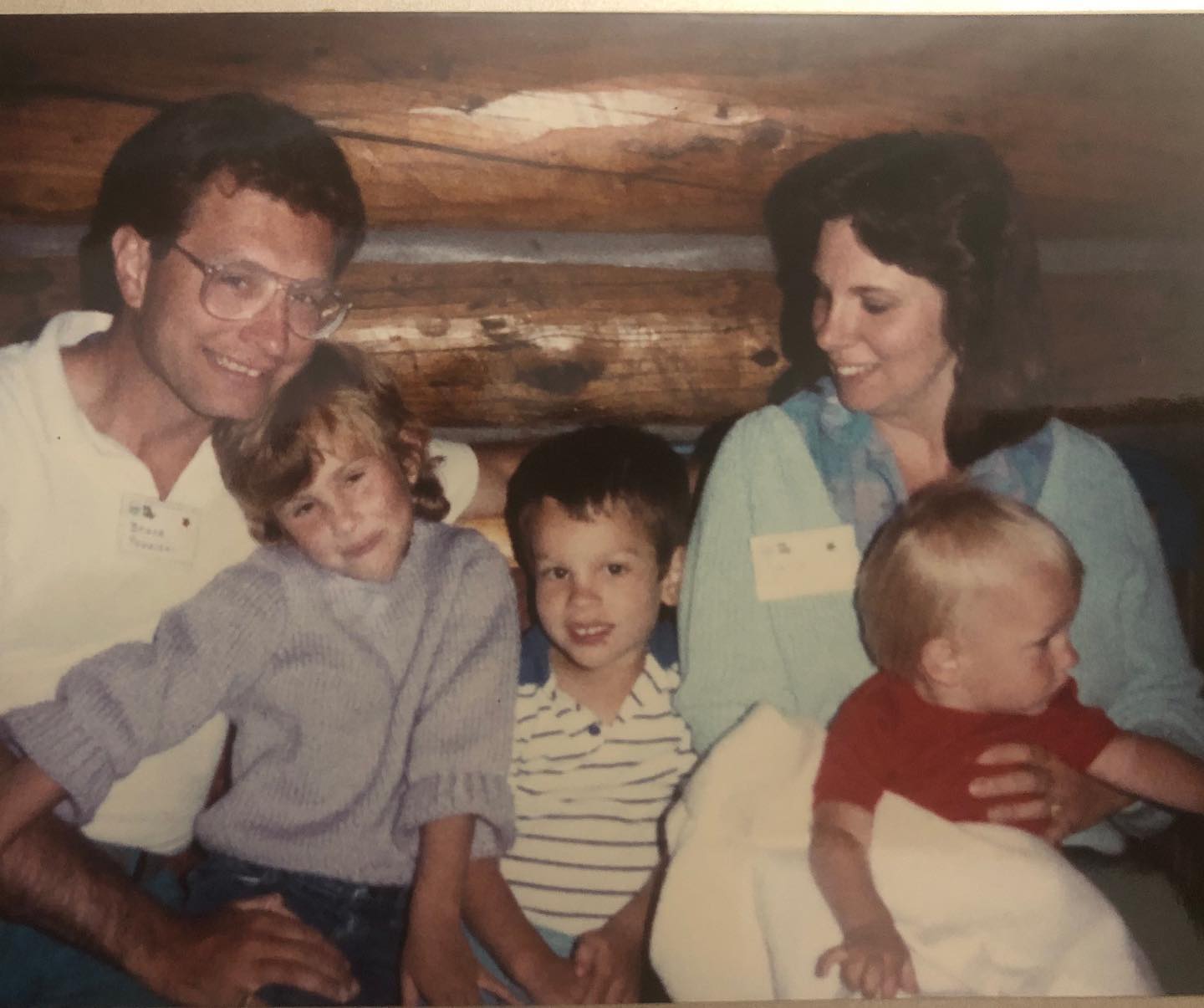

Circa 1990

I think that shift felt especially fulfilling because we had never been close when I grew up. She was a nurturing mother, to be sure, but we lacked the mother-daughter spark that seemed to draw so many of my friends and their mothers closer together.

I didn’t talk to her about boys. I didn’t talk to her about sex. I didn’t tell her when I had a falling out with friends. My senior year of high school, I drove to a dress boutique after school one day and purchased a prom dress with money I’d made from a part-time job. Upon seeing it, my mom exclaimed “Why didn’t you tell me you were going? I wanted to help you pick that out!” I remember feeling surprised, and kind of bad, about it. She had never shown interest in those types of things before and it hadn’t even crossed my mind to ask her to come – or to pay for it.

Fast forward to 2010: Perhaps as my friends and their own mothers were growing apart, my mother and I were finally getting our chance at that connection. The timing was finally right.

Until it wasn’t.

In March of 2019, my mom was diagnosed with moderate Alzheimer’s disease. She was in throes of it for at least a year leading up to that point, and on a steep decline for at least five years before that. The window of time that I thought was going to be decades-long on that Mother’s Day morning was actually just a few short years.

The Downturn of the Mind

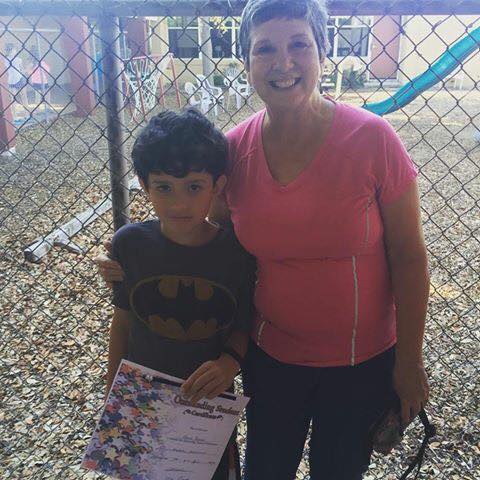

I first started to notice that my mom was acting strangely when she came to visit after the birth of my third daughter, Teagan, in 2014. By then I was living in Florida again — married, with five children under my roof through a combined marriage. She came down often to visit us, flying alone when my dad needed to work. She had recently retired from a job with the State of Indiana and was debating getting a part-time job that was less stressful and more social than her previous career. In the meantime, she came to visit us a lot and it was nice.

She was always a little quirky in general, even as I was growing up. Making up words for things, putting dishes in different places each time she washed them (I have this trait too) and just being generally silly. It’s always been endearing and she was ALWAYS sharp. Even in her goofy moments, I knew I had a really smart mom — who just happened to know how to make us laugh.

I think that silliness covered some of her dementia symptoms for awhile. Forgetting things, leaving things behind, wondering what she was supposed to be doing. When she visited me in Florida, it was even easier to write off her seemingly flaky behavior as her being away from home, disoriented in a different place that was bustling with young kids. It’s hard to think straight in this house, on a good day.

When Teagan was a few months old, my mom decided to take her for a walk in our Florida neighborhood. When I’d lived in Chicago, she would set out on walks with my oldest daughter, then a toddler, and return hours later to talk about their adventures.

It was four years later, but the scenario was similar enough. A spry grandmother wanted to take her latest grandchild on a neighborhood walk, on a beautiful, breezy Florida day. So my mom strapped Teagan to her chest in my baby sling and set out. I asked her which direction she was going and she said “towards the beach, of course” which is a straight half-mile shot from my house, and back.

An hour went by and I knew it was getting close to needing to feed the baby so I walked part of the route to the beach to find them. They were nowhere in sight. I walked home to see if they had arrived back but they were not there. I called my mom’s cell phone and heard it ring in the bedroom where she was staying. Panic crept into my throat. Where had they gone? Were they okay?

I hopped in my vehicle and started riding around the neighborhood. My husband Brant stayed back with the other kids. He said he’d call me if they showed up while I was out looking. I went by the beach, parked and looked down the stretch of sand, and saw no one. I drove around for what seemed like an entire day (but was likely more like 15 minutes) before I spotted my mom, talking to another woman in a driveway, about a half mile away from my home in the opposite direction of the beach. I pulled up and could hear the woman giving my mom directions.

My mom saw me and immediately beelined for the vehicle, hopping in the passenger seat with the baby still strapped to her chest. I started driving home.

“Well it’s about time you picked us up. How long was I supposed to be out walking around with her?” my mom snapped.

“I didn’t know you wanted to be picked up… you left your phone at the house…” I replied, confused. Was I in trouble for something?

“I can’t believe you would just leave me with your kid for so long.”

I wrote it off that she was embarrassed at getting lost. My mom seemed happier once she was home and had some water. She played with the older kids happily the rest of the visit, though I kept the baby at a distance. I believed I had done something wrong — imposed on her somehow — and spent the following days trying to make up for that.

But the same bizarre behavior continued to rear its head, and with more intensity, each time she visited. A public relations project I worked on for a few years took me to San Francisco at the end of January each year. For a few years my mom would fly in the week before, hang out with me and the kids, then help my husband while I was gone.

During January 2016, my mom came just a day before I left — and planned to stay for the entire week when I returned. My dad was going to drive down from Indiana a few days later to see us for a bit before traveling home with her. I spent brief moments with my mom before I caught my flight across the country.

By the next day, Brant texted me to say that my mom was having a hard time. She seemed confused and kept asking when she was going home. She sat with her suitcase in the living room, asking when my dad was going to “pick her up.” She seemed happiest doing dishes but just kept doing them, over and over, apologizing to my husband that she was “probably doing them wrong.”

Brant could see that something was off with her but he didn’t know what to do. He wanted her to be happy while she visited but she was restless, confused, near tears most of the time. When I got home to “save the day” she wasn’t much better for me. I spent most of the remaining days reminding her my dad would be there soon and trying to get her to engage with my kids, who she wanted nothing to do with. This was tough for my kids, who often looked forward to these visits from their silly Grandma Sally. We told them that grandma just needed some space and to respect that.

I tried gently to speak to my dad about her behavior when he arrived. At the time I wondered if we had truly done something to offend her, but he brushed it off (plus he was busy with my mom– who seemed to completely improve when he arrived — and his five grandkids). It wasn’t until they had left to return to Indiana that Brant and I both voiced our concern to each other over what we thought we saw — a woman with undiagnosed dementia.

It would be another three years before that diagnosis was official, with emotions at all-time highs between myself, my brothers, my dad and my mom herself. We all had opinions about what was going on with her — ranging from low-level stress to wondering if she had suffered a stroke at some point.

Through it all — and to this day — my dad remained a saint. Hugging her multiple times per day when she would start to cry, reassuring her constantly that he was not going to leave her, constantly reminding my brothers and I that he was still her keeper and that we needed to respect their boundaries. He started paying closer attention to what she was eating and ensuring she got out each day to swim at the local YMCA or at least go on a neighborhood walk. She started riding with him to work when we he would visit properties on which he was the general contractor.

On a Thanksgiving visit to Indiana in 2018, I was finally able to convince my dad to let me help arrange some preliminary appointments to figure out what was happening with my mom.

“For her sake, more than anything, ” I assured him.

After years of refuting my help, my dad acquiesced. He would allow me to arrange those meetings but all of the decisions still remained in his, and my mom’s, control. It was an arrangement I could agree to uphold.

We got the diagnosis we expected a few months later. Though it stung, having a name for what we were experiencing as a family and a treatment path was a relief. The tense question of “what should we do about all of this?” had been answered. It was now time to educate ourselves.

I Didn’t Know That Alzheimer’s Kills

As I started to research more about dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease specifically, I realized very quickly that what I thought I knew about these problems was very limited. The first was that Alzheimer’s is one form of dementia — the most common — but there are others.

My maternal grandmother fell into dementia in her later years, with it showing its worst in her late 70s. She died from congestive heart failure. I was there when it happened, up a few times the night before administering morphine drips as the Hospice nurse had directed before leaving her with us the afternoon prior.

We knew my grandmother had passed before we walked into the room around 6 a.m. the next day because we couldn’t hear the heavy, labored breathing that had been so loud leading up to the days prior. It was quiet. My mother and I went in the room together, both of us realizing we weren’t sure what to do next.

My mom grabbed her notes from the bedside table and frantically scrolled through them.

“They told us to call Nancy from Hospice, no wait… call 911… no… wait…”

Eventually we called Hospice and the wonderful person on the phone walked us through next steps.

It wasn’t funny but no one really preps you for what to do in the moments after you discover a person has died right under your nose — so we laughed. Then cried.

My grandmother died from congestive heart failure. I knew that she had Alzheimer’s too but that just seemed like a cruel joke that had to do with the aging human body. It was almost a part of her personality. It wasn’t what killed her.

So I didn’t know that a person with Alzheimer’s disease can actually die from it — if something else doesn’t kill that person first.

Alzheimer’s is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and many experts believe that underestimates the true Alzheimer’s deaths that can often be attributed to other issues, like pneumonia. More Americans die directly from Alzheimer’s than breast and prostate cancers combined according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

More than 5 million Americans live with Alzheimer’s and one in three seniors dies with Alzheimer’s or another type of dementia. A study from Rush University Medical Center predicts that by 2050, more than 13 million Americans will be living with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia.

The life expectancy for a person with Alzheimer’s varies greatly (believe me – I’ve scoured the internet trying to find a concrete answer to no avail). The ranges I’ve seen go from three to 20 years. Of course the age of the patient and the severity at diagnosis play into it. Some experts say that patients who are physically healthy when Alzheimer’s is diagnosed can live for up to 15 or even 20 years.

The way that Alzheimer’s kills is heart-wrenching. It gradually shuts down parts of the brain during the degeneration process, impairing function like breathing and swallowing. Eventually the disease shuts down something important enough to bodily function, like major organs, to kill the person.

My mom was only 65 at the time of her diagnosis, but we believe she was at least five years into the disease, if not longer. Her heart, lungs and the rest of her body are healthy, with normal degeneration for her age. The rapid acceleration of her disease, without medication for several years of it, means that we are facing the potential reality of this disease being the thing that takes her life. That was a complete shock to me.

How can this be? How has no one figured out how to fix this yet?

When I first heard the diagnosis, I had visions of her at 95, grayer than today, with more beautiful wrinkles in her hands and face, sitting on her front porch talking nonsense to whoever would listen — or to herself. But at best, we’re looking at 85 years total on this earth for her — based on the absolute longest life spans I’m seeing in my research. At worst… well, I can’t even bring my own brain to reconcile that.

I didn’t know Alzheimer’s can kill — and does.

What I’m Doing Now

I think the first thing that people do when something bad is happening with a loved one is to look at how it will affect their own lives. It sounds selfish but it’s just human nature. For me, the knowledge that my mother has dementia, just like her own mother had, is frightening on a personal level.

Alongside internet searches I conducted on the disease itself and what it means for my mom, I looked for as many details about genetics as I could find. What were my chances of having the disease myself? What lifestyle factors contribute to it? How much time did I truly have until this would come knocking on my door?

My internet searches on genetic propensity and sure-fire prevention tips were about as widespread as what I could find on life expectancy. Even the experts in the field seemed to disagree on major points. Some studies show that high stress in middle age can trigger the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Others say drinking coffee keeps it at bay. Others swear by a Mediterranean diet.

Once I gathered as much info as I could from as many reliable sources as I could find, I came up with a basic outline for Alzheimer’s prevention that goes something like this:

Alzheimer’s disease may or may not be preventable but eating whole foods and avoiding processed ones — along with prioritizing daily exercise, not smoking, limiting alcohol intake and reducing stress — seems to stave it off and even reduce symptoms once the disease has taken hold.

So basically if you live a generally-accepted healthy lifestyle, you might not end up with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia.

It is frustrating when there is not a clear-cut answer to a problem. Like many obstacles in life, it would be great to take a magic pill and watch Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia disappear. The not knowing haunts me.

On really tough days with our five kids, I’ll say to my husband, “Remember — they are going to give us grandchildren one day.” It’s not an immediately gratifying reason to be grateful for our brood, but it’s a reason.

Now I often wonder if I’ll know those grandchildren. If I’ll have the time — the cognitive time — to be with them. Will I be able to take them for walks to the beach? To babysit them so my kids and their spouses can have date nights? To show up to all of their games, performances and accomplishments? To tell them how I proud I am of every little thing they do?

I wonder about the accomplishments of my own life, aside from being a mother and potential-future grandmother. Do I have time to finish all of the writings I have scribbled in notepads or half-written in Google Docs? Will I leave the legacy of words that I always assumed I would eventually get on paper? Am I spending the time in my life wisely? Or taking for granted that I will always have more of it?

These days the threat of Alzheimer’s disease guides my every move. I eat less grains and more healthy fats. I exercise every single day. I visit the beach and breathe in the salt air. I say “no” to work that doesn’t ignite my spirit. I value quiet, non-productive time with my kids, my husband and myself. I try new things, even if they scare me. I sing a lot. I’m writing more of my own work, even if it means declining paid work from others. I’m trying to say “I love you” and “I’m sorry” more often. I let go of minor annoyances quickly. I journal about gratitude.

These are things that have improved the immediate state of my life and that I believe will improve the long-term quality of it. I want to know my grandchildren. I’m fighting for that now.

As for my mom, the medication seems to be helping her symptoms and most days, she’s very happy. She clings to my dad and he’s game for it. Though we all want him to transition to at least a little bit of outside help, he has adjusted to the new phase of their relationship with increased fervor and unconditional love. If he’s grieving her Alzheimer’s disease, he’s doing it privately, as is his right.

The grief I feel is different from his, as mine is a grief for things that never quite happened. I grieve for the lost moments of my childhood and young adult life that she and I can never get back. I grieve for my children’s accomplishments that my mom will not ever truly comprehend. I grieve for all the Mother’s Day brunches of the future.

But in that grief is self-realization. I don’t have the time that I think I do — none of us do. Living my best life for myself and for my family, right now, is the best way to live it. Say what needs to be said, today. Write what needs to be written, right now. Hug the people you love, every chance you get. Embrace the version of you that exists, in this moment.

And for goodness sake, don’t treat time as a renewable resource.

Katie Parsons is a writer, editor, podcaster and actor who lives on Florida’s Space Coast. She is the co-author of The Five Year Journal, available on Amazon. Visit her website ByKatieParsons.com for more information or contact her at katie@mumblingmommy.com.

Category: HealthTags: Alzheimer's