When I was thirteen years old, I fell in love. No, it wasn’t with a boy (this time), but with a novel: A Wrinkle in Time. This book had everything a shy, geeky, brunette girl like me could wish for: a shy, geeky, brunette heroine (who gets the boy!), adventure, fantasy, religion, politics, and a dash of humor. Like thousands of girls before me, I identified strongly with Meg Murray and have loved Madeline L’Engle’s works ever since.

When I was thirteen years old, I fell in love. No, it wasn’t with a boy (this time), but with a novel: A Wrinkle in Time. This book had everything a shy, geeky, brunette girl like me could wish for: a shy, geeky, brunette heroine (who gets the boy!), adventure, fantasy, religion, politics, and a dash of humor. Like thousands of girls before me, I identified strongly with Meg Murray and have loved Madeline L’Engle’s works ever since.

As a young adult, I discovered L’Engle’s nonfiction works: her Crosswicks journals, her writings on Christianity, and my favorite, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith andArt. Her generous theology, sense of wonder, and love of creativity resonated with me. Here at last was the grown-up Meg Murray! But for all my adoration, I felt a touch of anxiety, too. In her autobiographies, L’Engle somehow managed to have the perfect marriage, a celebrated writing career, and an affectionate family. She even got to spend her weekdays in New York City and her weekends in the country. Her life seemed to be the best of all possible worlds, and her books implied that if you were on the right path, you would not have to “choose” between career and family.

While reading these books, I was a newly married graduate student working to live out my childhood dream of being a writer: poetry, short stories, plays, etc. I took every workshop offered at my school, twice. I didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. And (surprise!) the first years of marriage aren’t that easy either. Where had I gone wrong? What would Madeleine L’Engle do?

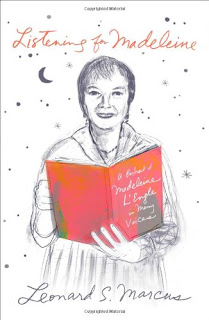

Ten years and two kids later, I spend much less time worrying about how my life “should be” and simply live it. But I still couldn’t resist picking up Listening for Madeline at the library the moment I recognized the face on the cover. I had no idea how eye-opening it would be.

Listening for Madeline is not your typical biography. It’s more like a Chuck Close painting: fifty separate interviews, fifty distinct images of the same person, somehow coalescing into a whole. Turning the pages, I was amazed at the seeming contradictions. One person gushes about Madeline’s warmth; the next complains that she could be cold and exacting. Young writers and students talk about her role as a mentor and surrogate parent, willing to take any promising young person under her wing. Yet others who knew the whole family describe a mother who wanted her children to be seen and not heard, who found it easier to connect to strangers than to her own family. Perhaps the most shocking information is that her marriage to Hugh Franklin was often tumultuous and, on his side, unfaithful.

What happened to that perfect life? It didn’t exist. Apparently Madeline’s autobiographies glossed over “the truth” of her life to paint a picture of a better life, perhaps the one she wished she had. Her children claim that her autobiographical works were less grounded in reality than her novels. However, as at least one interviewee explains, L’Engle did not grow up in the age of tell-all confessionals. Her generation was expected to hide the dirty laundry of their lives.

Reading the book, I also experienced conflicting emotions: surprise, sadness, and even a little relief. My hero wasn’t perfect; she didn’t “have it all.” She had to choose between work and family, and she chose her work. We still debate the work-life balance for women, and she lived it in the 1950s and 1960s, with no iPad, no telecommuting, and no concept of a “work at home” mother. My husband asked me if I lost respect for her work, knowing that she fudged the details of her life to make it sound better than it really was. No, I said, it just shows that she was human: flawed, full of contradictions, and striving, but not managing, to be better than she was. Just like the rest of us.

Let’s connect on social media too:

Mumbling Mommy on Facebook

Mumbling Mommy on Twitter

Mumbling Mommy on Pinterest

Category: Book Reviews

Tags: Elizabeth